Definitions drive debates: What we mean by "global cooperation"

by Laura M. Browning

We’re 10 months into the global coronavirus pandemic, and each passing day reinforces hard truths about our world: Climate change is threatening millions of people. With white supremacy gaining strength, systemic racism can no longer be ignored. Authoritarianism is emerging in historically democractic states. And as we look for both hope and practical solutions to our current crises, Doha Debates asks the question: Do we need new global institutions to usher in the kind of global cooperation necessary to face these crises? Or can we reform, rather than dismantle and rebuild? Solutions start with definitions, so here’s an overview of what we mean by “global cooperation” within the context of modern history and the current coronavirus pandemic. Keep these on hand for our virtual debate on September 20, 2020.

For the purposes of understanding global infrastructure and institutions, the modern era begins as World War II ends. That aftermath must have felt similarly bleak to today, with more than 50 million lives lost and the first atomic bombs deployed. In the war’s final stretch, 40 some countries met in the U.S. in Bretton Woods and laid the foundations for global institutions we still rely on today: the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. A year later, after the war ended, the United Nations was formed by the victors, replacing the League of Nations.

To say that the world was different then is to understate the sheer volume and ingenuity of the technological and creative innovations of the late 20th century. When representatives of those countries met at Bretton Woods, the leaders were living in a world where a vaccine for polio, which affected nearly half a million children a year, was still a decade away. Marvel Comics wouldn’t invent the Spider-Man or Incredible Hulk characters for nearly two more decades. The ENIAC computer, completed in 1946, weighed 30 tons and was housed in a 50-foot-long basement. And today? Most forms of polio have been eradicated, the Marvel Cinematic Universe is more than 20 movies long and a fingernail-sized microchip is more powerful than ENIAC. All of which is to say: The world in which the foundations of these global institutions were laid was vastly different to what we know today, and global cooperation looked very different 75 years ago.

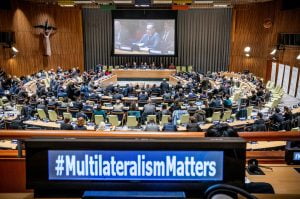

The Bretton Woods institutions were founded on multilateralism, which simply refers to multiple countries working together — something that is clearly necessary in order to control the current coronavirus pandemic. The Bretton Woods Conference lasted most of July 1944 and was attended by 44 countries, who were already anticipating the loss of the Axis powers in World War II.

Global institutions have been founded more recently, too. The G20, or Group of 20, is relatively new, founded in 1999 to foster cooperation among finance ministers and central bank governors, representing about 80% of the world’s economic output. In 2008, when the financial crisis gripped the world, the G20 was elevated to include heads of state, who first met in person that year. Some see the creation of such a group as an implicit suggestion that the United Nations lacks the resources or political will to effectively protect the world from challenges. Could the G20 or other similar groups be more effective? Or would similar institutions be too exclusive, keeping politically or economically marginalized countries from participating?

One of the forces working against more globally cooperative institutions is right-wing populism, which has been rising in many democratic countries, including the UK, U.S., Brazil, Hungary and Poland. The term “populism” originated in the late 19th century in the United States, when a political party, called the People’s Party or the Populist Party, gained a small but meaningful foothold. Then, as now, populism espouses an us vs. them mentality in which the ruling political classes are seen as out-of-touch elites. Although “populism” used to be seen more frequently in academic settings, 2016 — bookended by the Brexit vote and the U.S. presidential election — saw the term enter the mainstream. Cas Mudde, a Dutch political scientist who has written extensively about populism, puts it into a fairly simple binary: populists see themselves as “pure people” versus a “corrupt elite.”

Tensions over social issues and political divides have also led to civil unrest, an admittedly vague term that has been used by the media to describe a range of protests and riots. The primary movers of civil unrest have been growing anti-racists movements like Black Lives Matter, and the countervailing forces of nationalism and right-wing populism. As progressives take to the streets in peaceful protests — calling on their leaders to address systemic racism, anti-immigration policies, climate change and other issues that can only be solved with global cooperation — nationalist forces embrace slogans like “America first.”

Global south, a term you’ve heard if you’ve watched or attended other Doha Debates, refers generally to Latin America, Asia, Africa and Oceania. Jason Hickel’s excellent video (below) illustrates how the flow of money between the global north and south isn’t as altruistic as the global north would have us believe. When we speak of global inequality in broad terms, it’s defined by this north-south divide. Because the global institutions of the post-WWII era were largely founded by the biggest players of the global north, the global south is often underrepresented on major global issues that disproportionately affect them.

Here’s Why Foreign Aid Is a Scam

Given that the last 75 years have heralded not only enormous innovation but also increased attention to social justice and inequality, “global cooperation” looked very different in 1944 and ’45 than it does in 2020. Scientists knew about at least some of the dangers of climate change by the late 1970s, but it has since become an emergency requiring immediate global action. People around the world are increasingly concerned about justice for people who have historically been marginalized. True multilateralism today would involve more than just the world’s wealthiest economies, and would prioritize gender and racial representation. Are the institutions and infrastructures we built in the mid-1940s capable of seeing us through a global health crisis, a climate crisis and all the inequalities exacerbated by them? Join the conversation and watch the full debate online on September 20, 2020, at 10 a.m. Doha / 5 p.m. ET on Twitter, YouTube or Facebook.