How definitions drive debates: What we mean by "capitalism"

Most of us have been living and participating in capitalism since birth, as consumers and workers, so we know it as the sole standard; most economies are built on some form of capitalism today. But this free market economy hasn’t been the only way of life: A look at history shows how the long and sometimes bloody transition from feudalism to capitalism developed to address a growing population. Land, labor and money became commodities, and new roles and class structures and jobs were created, giving us a glimpse of the ways that economics and power are intertwined. Now more than ever, these descriptors of economic systems — capitalism and socialism — are gathering political and cultural weight. Can capitalism solve the 21st century’s most pressing challenges — a burgeoning population, the shrinking of natural resources, the climate crisis, the widening wealth gap — or is it becoming unsustainable? Is it time to transition again?

Solutions start with definitions, so here’s an overview of the essential meanings of the major terms in our live debate on October 23, 2019, with guest speakers Ameenah Gurib-Fakim, Anand Giridharadas and Jason Hickel. (They know their stuff!) Merriam-Webster notes, “Communism, socialism, capitalism and democracy are all among our top all-time lookups, and user comments suggest that this is because they are complex, abstract terms often used in opaque ways.” It’s important to distinguish each, and it’s also important not to fall into the trap of false equivalencies.

Capitalism is an economic system based on private ownership and the opportunity for an individual to own the means of production and the product. You get to decide how you’ll earn money (if you’re privileged enough). The driving force is profit. Under ideal circumstances, capitalism accounts for supply and demand properly by incentivizing healthy competition, proponents argue, while reducing waste by efficiently using resources and stirring innovation and industrial growth. Factories can make more shirts for more people at lower prices (also known as mass production), rather than a lot of people making a few shirts for a king and earning no wages (also known as slavery).

Historically, capitalism has improved the quality and length of life for many people by creating job growth and benefits for workers moving from countrysides to opportunity-rich cities. But capitalism’s rosy benefits for some people come with extreme risks and costs for laborers with the fewest protections and privileges. Markets concentrate toward monopolies, as people in power accrue more power, and the opportunity for exploiting underpaid laborers and people in poverty is very high, with profound consequences, like the global financial crisis of 2007–2008. It turns out that work is not what’s rewarded — wealth is: Those at the top get most of the benefits of economic growth while everyone else becomes further marginalized. According to an Oxfam report, “82% of all wealth created in the last year went to the top 1%, and nothing went to the bottom 50%.” The cycle of consumption and production, and unchecked growth, encourages exploitation of natural resources: This past August, 26,000 fires — the most in a decade — were recorded in the Amazon rainforest so the agricultural industry could clear room for cattle and soy. Let’s not get started about plastics pollution.

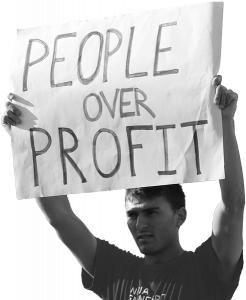

Can a new social contract be drawn to prioritize society over profit? Socialism is a broad ideology with many shades, lacking a precise and agreed-upon definition. At its core, it shifts from capitalism’s private ownership to collective, democratic ownership over the means of production. These days the words “socialism” and “communism” (one specific form of socialism) carry as many political and cultural connotations as economic ones. While socialism was born out of the idea that capitalism is inherently unfair, exploitative, hierarchical and individualistic, and that the gap between rich and poor must shrink, socialism is often spun and mischaracterized especially in U.S. politics by capitalists clinging to red-scare tropes popularized during World War II and the Cold War. There’s socialism as threat, and socialism as savior, an alternative to capitalism for people looking for a more distributive model than a “free” market that multiplies society’s inequalities.

For people who understand that we cannot have limitless growth on a planet with finite resources, degrowth is a new potential direction for rethinking economics — a path that distinguishes between “growth” and “prosperity.” The term “degrowth” was coined at a conference in Paris in 2008, defined as a “voluntary transition towards a just, participatory, and ecologically sustainable society.” It recognizes that the economy cannot grow indefinitely and that we must consume and produce much more efficiently, understanding and accepting our environmental limitations. One degrowth model, proposed by Oxford economist Kate Raworth, is the doughnut: It incorporates two major elements that are missing in classic economic theories: humanity’s social foundation (our basic human needs) and the planet’s ecological ceiling. The aim is to balance both, creating a circular economic system where reusability prevails.

The takeaway from historical evidence and contemporary theories is that capitalism doesn’t have to be the only standard. Is it built for today’s challenges, or is it due for sweeping changes? Join the conversation now and watch the live debate on October 23 @DohaDebates.

Watch the full debate

Capitalism